Strangest of all this, that the mad agony of grief, the passion of desolation that came upon me when our long partnership was dissolved for ever, should now be nothing but a memory, like other memories, to be summoned up out of the resting-places of the mind, toyed with, idly questioned, and dismissed with a sigh and a smile! What a real thing it was just ten years ago; what a very present pain! Believe me, Will, yes, I want you to believe this that in those first hours of loneliness I could have welcomed death; death would have fallen upon me as calmly as sleep has fallen upon my boy in the room beyond there.

Extravagant

You knew nothing of this then; I suppose you but half believe it now; for our parting was manly enough. I kept as stiff an upper lip as you did, for all there was less hair on it. Perhaps it seems extravagant to you. But there was a deal of difference between our cases. You had turned your pen to money-making, at the call of love; you were going to Stillwater to marry the judge`s daughter, and to become a great land-owner and mayor of Stillwater and millionaire or what is it now? And much of this you foresaw or hoped for, at least. Hope is something. But for me? I was left in the third-story of a poor lodging- house in St. Mark`s Place, my best friend gone from me; with neither remembrance nor hope of Love to live on, and with my last story back from all the magazines.

We will not talk about it. Let me get back to my pleasant library with the books and the pictures and the glancing fire-light, and me with my feet in your bearskin rug, listening to my wife`s step in the next room.

To your ear, for our communion has been so long and so close that to either one of us the faintest inflection of the other`s voice speaks clearer than formulated words; to your ear there must be something akin to a tone of regret regret for the old days in what I have just said. And would it be strange if there were?

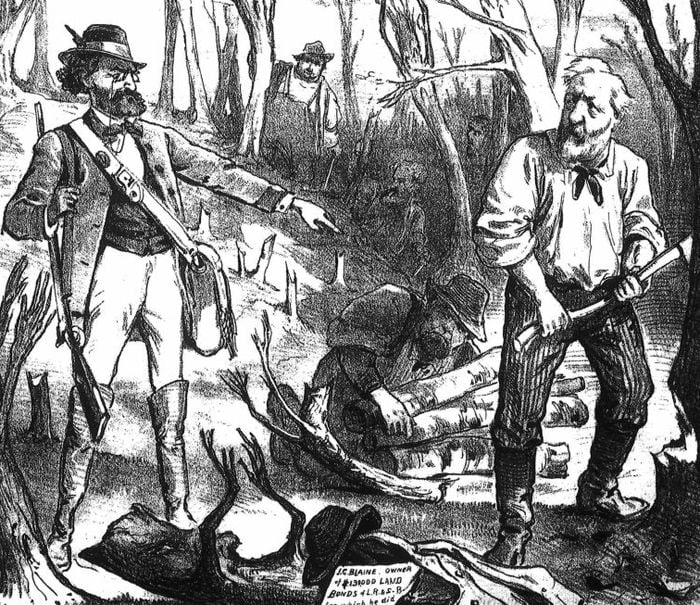

A poor soldier of fortune who had been set to a man`s work before he had done with his meager boyhood, who had passed from recruit to a place of a young veteran in that great, hard-fighting, unresting pioneer army of journalism; was he the man, all of a sudden, to stretch his toughened sinews out and let them relax in the glow of the home hearth? Would not his legs begin to twitch for the road; would he not be wild to feel again the rain in his weatherbeaten face?

Would you think it strange if at night he should toss in his white, soft bed, longing to change it for a blanket on the turf, with the broad procession of sunlit worlds sweeping over his head, beyond the blue spaces of the night? And even if the dear face on the pillow next him were to wake and look at him with reproachful surprise; and even if warm arms drew him back to his new allegiance; would not his heart in dreams go throbbing to the rhythm of the drum or the music of songs sung by the camp-fire?

Read More about Report of his Mission to Constantinople part 27